As a pastor, certain stories in the news don’t just pass by; they land squarely in your heart. The report about the Lighthouse Institute for Evangelism, a small storefront ministry in Long Branch, New Jersey, was one of those. When I read that the Church was being barred from a downtown commercial district because city officials felt its presence would blight their plans for an entertainment hub, it wasn’t a distant legal battle to me. It was a mirror reflecting the challenges so many of us in ministry face. It was personal.

This story captures a fundamental tension that defines much of modern ministry: the collision between our sacred calling and the often impenetrable labyrinth of government regulation. Across this nation, religious institutions serve as a critical safety net. As one guide for municipal attorneys rightly observes, “religious institutions fulfill a vital function in American communities, often stepping in to provide needed social services when the government is unwilling to or incapable of doing so.” From food closets to addiction recovery programs, we are driven by our faith to fill the gaps. These conflicts force a question our society is still wrestling with: how do we balance the good that ministries do with the civic order that regulations are meant to protect?

This work flows directly from a scriptural mandate that echoes in the soul of every believer: the call to care for “the least of these.” It is a command that is profoundly simple in its wording but can become agonizingly complex in its execution. When the simple act of offering help becomes a matter of zoning codes that prioritize commerce over compassion, a pastor is caught between the law of the land and the law of love.

The struggle of the Lighthouse Institute is a powerful and poignant example of this timeless conflict that demands our attention.

The Story: A Church “Treated Like a Blight” for Its Mission

In Tong Branch, New Jersey, the Lighthouse Institute for Evangelism sought to establish a small storefront church to serve the disadvantaged. It was an act of faith in its purest form. But this act of compassion was met not with welcome, but with exclusion. The Church purchased property in a commercial district. Still, the city council denied its permit, explaining that a church would “destroy the ability of the block to be used as a high-end entertainment and recreation area.” A New Jersey statute prohibits issuing liquor licenses within 200 feet of a house of worship, and the city worried the Church’s presence would interfere with its economic revitalization plans.

In Tong Branch, New Jersey, the Lighthouse Institute for Evangelism sought to establish a small storefront church to serve the disadvantaged. It was an act of faith in its purest form. But this act of compassion was met not with welcome, but with exclusion. The Church purchased property in a commercial district. Still, the city council denied its permit, explaining that a church would “destroy the ability of the block to be used as a high-end entertainment and recreation area.” A New Jersey statute prohibits issuing liquor licenses within 200 feet of a house of worship, and the city worried the Church’s presence would interfere with its economic revitalization plans.

In the city’s eyes, the ministry was not an asset but a liability. One court aptly described the situation as a “reverse urban blight case,” where instead of bars blighting the area, the Church was seen as blighting the bar and nightclub district.” A church, a place of sanctuary and hope, was being treated not just as a nuisance, but as a contagion threatening the neighborhood’s commercial health

To hear of a ministry being treated like a blight for its desire to serve is jarring. It creates a profound sense of spiritual dissonance. We are called to be a light in the darkness, a place of refuge for the hurting. To be told your light is not welcome because it might dim the neon signs of a planned entertainment zone is to feel the weight of a world that doesn’t always understand the heart of the Gospel. As I reflected on the ministry’s ordeal, a thought kept returning to “e: “We preach compassion, but sometimes the law treats compassion like a cr” me.”

It’sn’t JChurch’s story in a New Jersey town. For those of us in ministry, it reflects a struggle we all know and a tension we all feel.

My Personal Reaction as a Pastor

Reading about the Lighthouse Institute evoked a mix of emotions that are all too familiar to those of us in ministry leadership. It’sn’t just another news item to be debated; it strikes at the very core of my identity as a pastor and, I believe, the Church’s identity itself.

My reaction was threefold. First came a deep sense of empathy for the pastor in New Jersey, who sought only to bring hope to a community but was instead told his ministry was bad for business. Then came a wave of frustration—a frustration with bureaucratic systems that can be so rigid and so focused on tax revenue that they stifle the very charity our communities desperately need. Finally, that frustration gave way to a renewed resolve. Stories like this don’t discourage me; they reinforce my conviction that the work of Churchurch is more vital now than ever, and we must press on, regardless of the obstacles. I can’t count the number of times in my own ministry when the urgent need for compassion has run up against logistical hurdles or regulations. A sudden cold snap brings a family to our doors late at night. The aftermath of a house fire leaves a neighbor with nothing. In those moments, the immediate, human need is overwhelming. Yet, it is often followed by a cascade of secondary concerns: neighbor complaints about noise or traffic, worries about property values, or the realization that our buildings aren’t perfectly zoned for the impromptu service we are providing. These objections, often categorized by the secular term “MBY” (Not In My Back Yard), can create immense pressure to choose compliance over compassion. This frustration is precisely why the “he “Equal T”rms” provision of federal law is so necessary—it prevents cities from allowing a community theatre or a private club while telling a church it is unwelcome.

In these moments, churches are uniquely positioned to be the first responders of the soul. We can act with an agility and a heart that government agencies, for all their resources, often cannot. Ministries like Lighthouse Institution don’t supplement official services; they step into the void when no one else will, especially in times of crisis.

This experience—the clash between the call to help and the codes that hinder—is what makes this story so personal. And it forces us to ask the foundational legal question at the heart of this and so many similar conflicts.

The Legal Question at the Heart of the Case

While the events in Long Branch feel intensely personal and pastoral, they are a microcosm of a critical legal debate playing out across America. This local zoning dispute raises a fundamental question about the scope of religious freedom for churches, synagogues, and mosques in the country.

The core legal question is this: Can a city apply its standard zoning and safety codes to a church’s activities in the same way it would to a commercial business, or does that action violate the Church’s constitutional right to the free exercise of religion?

The answer often hinges on a legal standard known as strict scrutiny, or, for those of us without a law degree, the highest level of legal protection a right can receive. When a government action is subjected to strict scrutiny, the government—not Churchurch—bears a heavy burden of proof. It must demonstrate two things:

- That its action serves “compelling governmental interest of the highest order, such as public safety against a grave and immediate danger. It is using “he in the “least restrictive manner” to achieve that interest, meaning there is no other way to accomplish its goal that would be less burdensome to the Church’s religious practice.

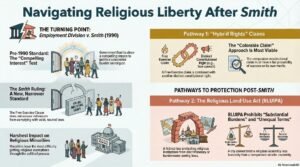

For decades, this high standard, established in the 1963 case Sherbert v. Verner, was the norm for protecting religious freedom. That changed dramatically in 1990 with the Supreme Court’s decision in Employment Division v. Smith, which held that the compelling-interest test did not apply”to “neutral, generally applicable laws.” This significantly lowered the bar for the government and weakened protections for religious exercise. In response to that ruling, a bipartisan Congress passed the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) in 2000. This crucial federal law was specifically designed to restore he compelling interest test for land use disputes, ensuring that local zoning decisions could not unfairly burden the Church’s mission.

This legal framework is more than just abstract doctrine; it is the arena where the on-the-ground reality of ministry meets the power of the state.

Compassion vs. Compliance — A Tension Every Ministry Faces

Let me be clear: churches are not seeking to be unsafe, irresponsible, or above the law. The tension between compassion and compliance is not about evading rules. It is about the profound difficulty of applying regulations designed for commercial buildings and predictable uses to the urgent, unpredictable, and often messy work of caring for human beings in crisis.

Of course, cities have a valid and compelling interest in enforcing fire codes, ensuring safe occupancy limits, and protecting public health. No church wants to put the people it serves in harm’s way. The problem arises when these codes are applied so rigidly that they effectively outlast the Church’s mission. This is where the law steps in. The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, or RLUIPA, defines the operation of a shelter or soup kitchen as a form of religious exercise; this means these ministries are legally protected from being regulated out of existence by a zoning code that was never designed for them.

Of course, cities have a valid and compelling interest in enforcing fire codes, ensuring safe occupancy limits, and protecting public health. No church wants to put the people it serves in harm’s way. The problem arises when these codes are applied so rigidly that they effectively outlast the Church’s mission. This is where the law steps in. The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, or RLUIPA, defines the operation of a shelter or soup kitchen as a form of religious exercise; this means these ministries are legally protected from being regulated out of existence by a zoning code that was never designed for them.

This is a nationwide phenomenon. The conflict in New Jersey is not an isolated incident. Consider these examples from across the country:

- In New Hampshire, a church was denied a permit to install an electronic sign to display religious messages because of a desire to maintain the town’s small New England village aesthetic.

- In Frederick, Maryland, a church was prohibited from leasing space in a business district, even though the city permitted a variety of non-religious assembly uses, such as private clubs, theaters, and reception halls, in the very same zone.

- In Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, a small congregation meeting in a school cafeteria was told it needed a special permit, a requirement not imposed on non-religious groups like civic organizations and theaters using the same type of space.

In each of these cases, the core argument remains the same: churches are not trying to avoid reasonable standards. We are simply asking for the legal system to recognize our moral and spiritual imperative to serve the vulnerable and to find ways to accommodate that mission, not criminalize it.

The protections enshrined in federal law don’t resolve this tension, but they do provide a hopeful path forward.

WRLUIPA’s Protections Mean for Churches Like Mine

The passage of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act is more than a legislative footnote; it is a beacon of hope and a source of profound legal clarity for ministries everywhere. It provides a powerful affirmation that our work is not only spiritually vital but also legally protected.

The practical impact of RLUIPA is immense. First, the “Equal T”rms” provision prevents a city from allowing secular assemblies, such as theaters or clubs, in a zone while excluding churches. This was the key issue in Frederick, Maryland, where the Department of Justice investigated the city’s prohibition on the Strong Tower Church operating in a business district. In response, the city amended its ordinance to treat religious assemblies equally, providing a powerful example of how the law can secure the Church’s rightful place in the community.

SecoSecoRLUIPA “Substantial Bu”den” provision, which triggers strict scrutiny, prevents a ministry from being incidentally regulated out of existence by codes that were never designed for its unique mission. A city cannot simply apply a one-size-fits-all ordinance and declare a ministry illegal; it must prove it has a compelling reason and that there is no less restrictive way to ensure public safety.

To my fellow pastors and church leaders, I offer this encouragement: view these protections not as an invitation to defy local laws, but as a framework for productive engagement. We should not see our local officials as adversaries. Instead, this is an opportunity to educate them and partner with them. Let us proactively learn our local codes, invite officials to consult, and work together to find “he leat restrictive means” of ensuring safety without sacrificing ministry. Our goal should be to find a path”to “yes “—a path where our cities see our compassionate work as an asset to be enabled, not a problem to be zoned away.

This legal clarity empowers us as leaders, but the responsibility to act on it extends to every believer in our pews.

A Personal Call to Action

The story of the Lighthouse Institute has deepened my commitment to the ministries that stand in the gap for the poor and marginalized in my community. It reminds me that this work is at the very heart of our faith, and it requires the support of the entire body of Christ. This is not just a job for pastors; it is a calling for all of us.

I urge you to support the local churches engaged in this vital work. Here is how you can help:

- Prayer: Pray for the spiritual and emotional strength of the pastors, staff, and volunteers on the front lines. Pray for their protection and for wisdom as they navigate complex challenges. And most of all, pray for the precious individuals they serve—that they would find not only help, but hope, dignity, and grace.

- Service: This work cannot be done without willing hands and generous hearts. Volunteer your time at a church-run social ministry, donate needed resources like food and clothing, or organize a group from your Church to provide a hot meal. Your presence and support can be powerful sources of encouragement.

- Advocacy: Use your voice respectfully and constructively. Talk to your own church leaders about how your congregation can engage with city officials. Encourage those officials to see local ministries as partners. Ask them to apply zoning laws with the flexibility and understanding necessary to protect, rather than punish, compassionate ministry.

For churches looking to engage in this work, I also suggest these practical steps to foster cooperation:

- Invite the local fire marshal for a consultative walk-through before a problem arises. Ask for their advice on how to make your space as safe as possible for serving people.

- Develop a formal safety and operations plan for your social ministries. Show your city you are thoughtful, organized, and committed to best practices.

- Present your case to the city council with clear documentation of the community need you are meeting. When officials see the faces and hear the stories of the people you serve, it transforms the conversation from an abstract zoning issue to a human one.

These practical actions are an essential part of our witness, elevating our service into a powerful reflection of our faith.

Conclusion — Faith That Stands Even When Challenged

Ultimately, the story of the Lighthouse Institute and so many others like it is about much more than zoning laws. It is about the fundamental right and biblical duty of the Church to put its faith into action through tangible acts of love. It is about whether our communities will make room for mercy, or zone it out of existence.

As I reflect on these cases, one final thought comes to mind: “When the law conflicts with love, we must shine even brighter. This ruling reminds us that compassion still has a place in our courts — and in our communities.” The legal protections afforded to churches are a powerful affirmation of a timeless spiritual truth: that our call to serve the vulnerable is not a peripheral activity but is central to our identity as followers of Christ.

The mission of Churchurch will always be tested. We will face challenges from a world that may find our expression of radical love to be inconvenient or disruptive. But the stories of faithful ministries across this country are a beautiful and timely testament to a faith that does not shrink from that challenge. It is a faith that is not broken by opposition, but is instead proven, purified, and strengthened through it.